Pita as Teacher: Bread Subsidy Cuts in Jordan, After Syria

02/18

Late last month Jordan agreed to cut bread subsidies, following increased economic strain as the country continues to absorb shockwaves from conflict in Syria and Iraq. The new prices, which took effect on the first of February, will increase the cost of taboon breads by 90-100 percent. Some claimed that the subsidies were aiding refugees more than Jordanian nationals, and some that the low bread prices encouraged waste. Either way the move points out a disparity in consumption habits across income lines, and most directly affects the poorer communities who are the largest consumers of the inflated products. Taboon breads, the category of large flatbread which pita falls under, are a staple for the lowest classes in Jordan (and across the Middle East),

and many rely on them for a majority of their daily caloric intake. The move further disables these more vulnerable communities, who are most reliant on government controlled food subsidies and regulations. There has not been a major price increase of bread in Jordan since 1996. It’s symptomatic of a boiling point of regional tensions resulting from the war in Syria, which has lowered domestic economic progress and foreign aid in the country, combined with the country’s lack of natural resources. The move will be implemented through a U.S. style SNAP program (which, ironically, is to be diminished by over 25% stateside in the next decade, through the GOP’s proposed budget cuts).

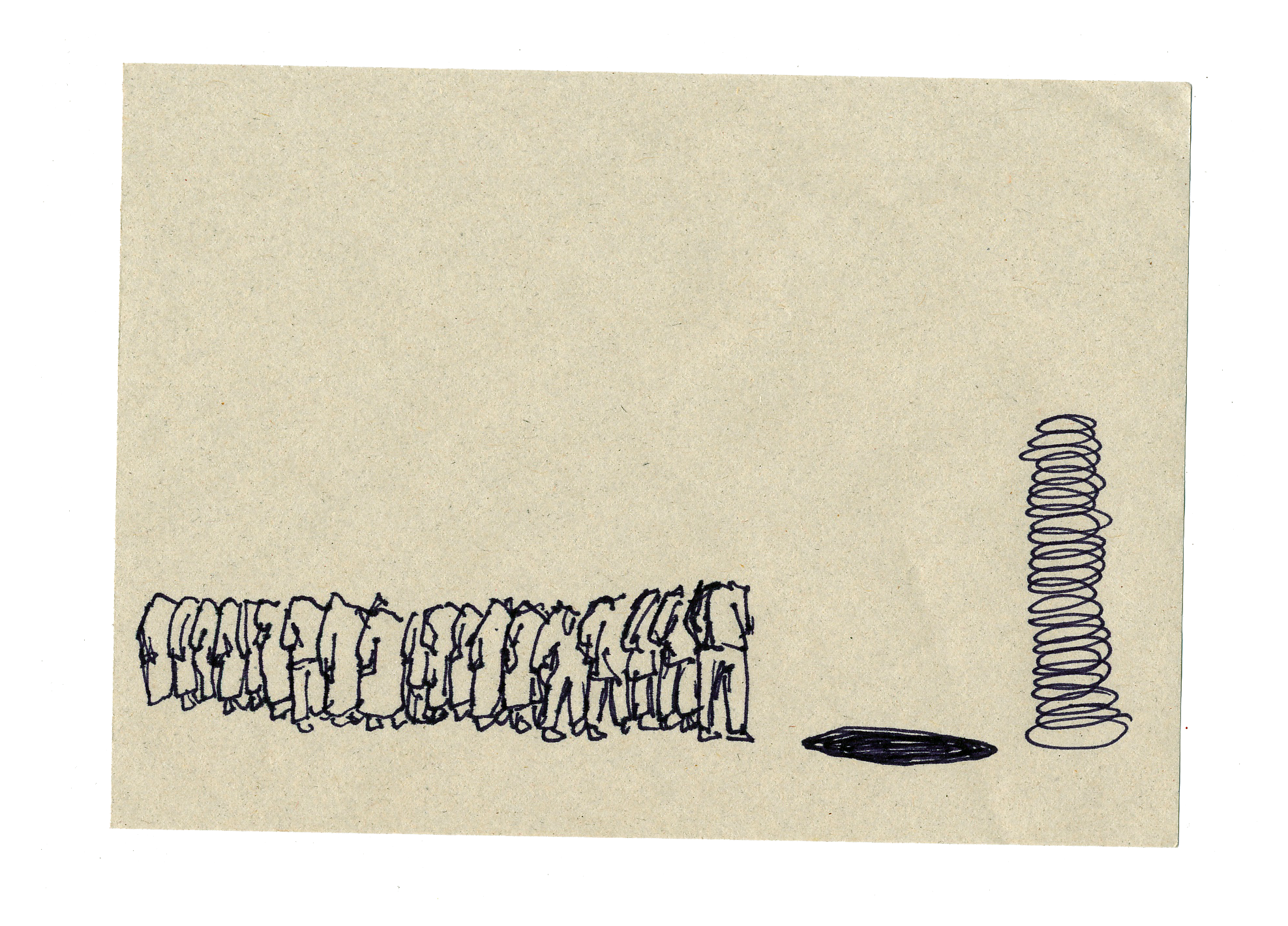

This feels like an apt time to recount the ways that Syria has shown us the barometric properties of bread during war, or in any country undergoing social transition. Bread emerged as a more powerful resource than oil when the Syrian regime attempted to control and bottleneck wheat and bread supplies, starting in the early days of the uprisings. Despite some input from international aid organizations, the government still held control over distribution, and bread began to be intentionally withheld from areas that were home to rebels. Bakeries and bread lines were targeted and bombed. Government bread and wheat slowed from daily deliveries, before the war, to once or twice a week. With the bread stream still in the hands of the regime, civilians, especially the poorer communities, lacked agency and control, remaining bound to whoever puppetted the flow of wheat. Quickly, a previously affordable food staple was draining what remained of Syrians’ bank accounts.

A chronology:

-In 2008, Syria had to import wheat for the first time following record-breaking poor harvests resulting from a prolonged regional drought.

-In 2011, protests erupted as wheat and bread supplies dwindled and farmers were put out of work. Villagers moved from rural areas to urban shanty towns.

-Despite government attempts to compensate through imports and policy changes, the unrest continued. The Assad regime made a disastrous attempt to regain control over the rebellions by bombing the increasingly long bakery lines resulting from the wheat shortage.

-Then, as Emma Beals writes in her thorough discussion of bread as political weapon in Syria, “The regime and the rebels battled for territory, including grain silos and bakeries in the northeast region, and when jihadist groups saw an opportunity in the chaos, they also sought control over these vital resources. The files of Haji Bakr, an Islamic State mastermind, retrieved by Der Spiegel, indicate that ISIS had a detailed plan on how to take control of the largest flour mill in northern Syria. Once ISIS did, the group applied a typically disciplined approach to the production cycle in an attempt to feed the populations in areas it controlled to win their support.” It should be noted as well, that this period also saw the arrival of “bread brokers”, serving as black market middle-men, buying bread in bulk and holding court in front of the many unpoliced bakeries, selling bread at an even higher rate than the already inflated prices inside.

-Systemic breakdown manifests all the way down the line, from seed and fertilizer distribution, to flour provisions, to the bakeries themselves- leading to a complete reliance on credit lines and imports from Iran, Russia and the US, making Syria reliant on foreign nations for food security for the first time.

-As always, there is some progress- humanitarian aid continues to take steps to support distribution and production and encourage growth in the domestic agricultural sector, following a model similar to that of the jihadists. People have begun circumventing government provided supplies and opting for any attempt at self-sufficiency, even using alternate seeds for flour. Supplies are also smuggled in from areas that support the regime and are still recipients of grain.

-Through all of this, multinational purveyors of industrial wheat reap the benefit of the increasing cost of flour. After all, only in the West, the land of gluten-freedom, are people relinquishing bread by choice. Distributors like Cargill and Glencore will always have customers.

-In 2011, protests erupted as wheat and bread supplies dwindled and farmers were put out of work. Villagers moved from rural areas to urban shanty towns.

-Despite government attempts to compensate through imports and policy changes, the unrest continued. The Assad regime made a disastrous attempt to regain control over the rebellions by bombing the increasingly long bakery lines resulting from the wheat shortage.

-Then, as Emma Beals writes in her thorough discussion of bread as political weapon in Syria, “The regime and the rebels battled for territory, including grain silos and bakeries in the northeast region, and when jihadist groups saw an opportunity in the chaos, they also sought control over these vital resources. The files of Haji Bakr, an Islamic State mastermind, retrieved by Der Spiegel, indicate that ISIS had a detailed plan on how to take control of the largest flour mill in northern Syria. Once ISIS did, the group applied a typically disciplined approach to the production cycle in an attempt to feed the populations in areas it controlled to win their support.” It should be noted as well, that this period also saw the arrival of “bread brokers”, serving as black market middle-men, buying bread in bulk and holding court in front of the many unpoliced bakeries, selling bread at an even higher rate than the already inflated prices inside.

-Systemic breakdown manifests all the way down the line, from seed and fertilizer distribution, to flour provisions, to the bakeries themselves- leading to a complete reliance on credit lines and imports from Iran, Russia and the US, making Syria reliant on foreign nations for food security for the first time.

-As always, there is some progress- humanitarian aid continues to take steps to support distribution and production and encourage growth in the domestic agricultural sector, following a model similar to that of the jihadists. People have begun circumventing government provided supplies and opting for any attempt at self-sufficiency, even using alternate seeds for flour. Supplies are also smuggled in from areas that support the regime and are still recipients of grain.

-Through all of this, multinational purveyors of industrial wheat reap the benefit of the increasing cost of flour. After all, only in the West, the land of gluten-freedom, are people relinquishing bread by choice. Distributors like Cargill and Glencore will always have customers.

Before the war, Syria was a self-sustaining agricultural center. The country was capable of producing enough wheat to support a hungry nation of avid bread eaters (the only country in the region able to do so). The combination of civil and environmental disruption created a parallel path between the war itself and Syria’s bread shortage, both a symbolic and literal destitution. So, does war affect bread or does bread affect war? Of course, Syria and Jordan are just a couple samples in a possible global study of the linkage between the two, with a particular focus on how violent unrest disrupts local economies.

As a catalyst for the bevy of bread-induced rioting, 2010 and 2011 saw the global price of wheat double. The aftershocks were felt around the world, especially in nations that truly rely on bread as “the staff of life.” Egypt and Algeria, along with Jordan, Morocco, Yemen and others, are all huge importers and consumers of wheat. The riots following the inflation of wheat prices and the resulting surge in costs can be seen in these nations as well, and offer further evidence/study of bread as gauge of the geopolitical climate.

The rise in the cost of a loaf of bread has never been the tide of good fortune. We are smart to keep our eyes to Jordan to see how yet another country reacts to the change.

Further Reading:

USDA FAS

Struggling to Perform the State: The Politics of Bread in the Syrian Civil War (paywall)

Emma Beals, Munchies

Reuters

Mother Jones

IRIN

ABC